Jan.11.2010

4:42 pm

by Ed Beakley

EEI#22 “What kind of war” -continued (8 of ?) – No Exit

Essential Elements of Information for a Culture of Preparedness

America has an impressive record of starting wars but a dismal one of ending them well.

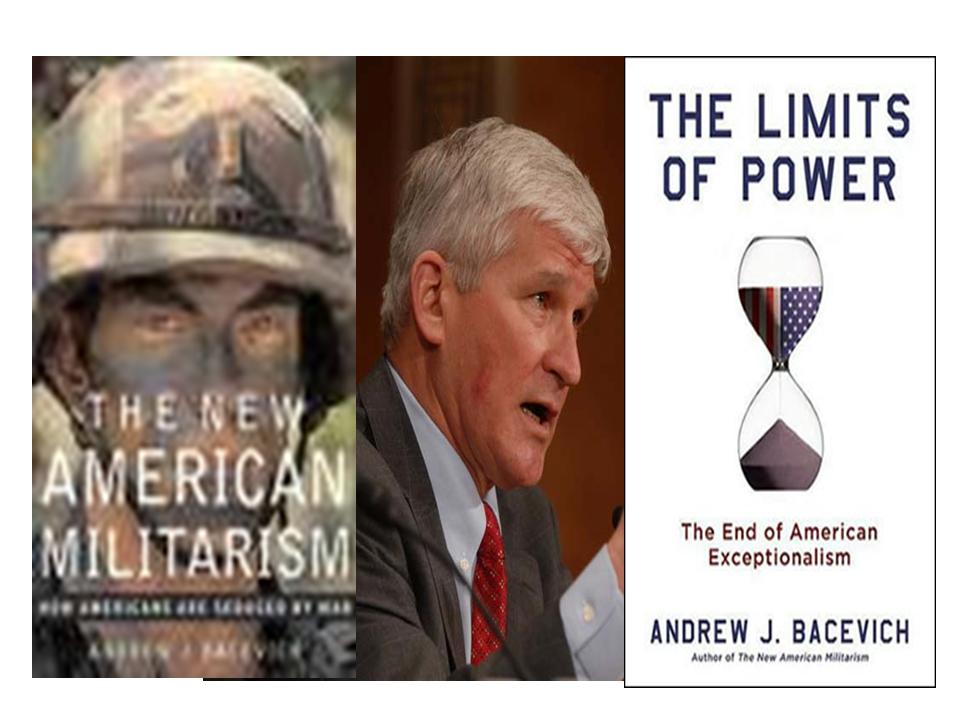

Andrew J. Bacevich is professor of history and international relations at Boston University. He is a retired Army Colonel, graduate of West Point, serving in Vietnam in 1970 and 71. In his books [The Limits of Power, The Long War, and The New American Militarism: How Americans are Seduced by War ], he is critical of American foreign policy in the post Cold War era, maintaining the United States has developed an over-reliance on military power, in contrast to diplomacy, to achieve its foreign policy aims. He also asserts that policymakers in particular, and the American people in general, overestimate the usefulness of military force in foreign affairs. Bacevich conceived The New American Militarism not only as “a corrective to what has become the conventional critique of U.S. policies since 9/11 but as a challenge to the orthodox historical context employed to justify those policies.” His new book Washington Rules: America’s Path to Permanent War is due out in the spring.

This article found on The American Conservative would appear consistent with his past writing and the excerpt is offered as yet another view of “what kind of war.”

No Exit (Excerpt)

by Andrew Bacevich

President Obama’s decision to escalate U.S. military involvement in Afghanistan earned him at most two muted cheers from Washington’s warrior-pundits. Sure, the president had acceded to Gen. Stanley McChrystal’s request for more troops. Already in its ninth year, Operation Enduring Freedom was therefore guaranteed to endure for years to come. The Long War begun on George W. Bush’s watch with expectations of transforming the Greater Middle East gained a new lease on life, its purpose reduced to the generic one of “keeping America safe.”

Yet the Long War’s most ardent supporters found fault with Obama’s words and demeanor. The president had failed to convey the requisite enthusiasm for sending young Americans to fight and die on the far side of the world …

… That the post-Cold War United States military, reputedly the strongest and most capable armed force in modern history, has not only conceded its inability to achieve decision but has in effect abandoned victory as its raison d’être qualifies as a remarkable development.

Since 1945, the United States military has devoted itself to the proposition that, Hiroshima notwithstanding, war still works—that, despite the advent of nuclear weapons, organized violence directed by a professional military elite remains politically purposeful. From the time U.S. forces entered Korea in 1950 to the time they entered Iraq in 2003, the officer corps attempted repeatedly to demonstrate the validity of this hypothesis.

The results have been disappointing. Where U.S. forces have satisfied Max Boot’s criteria for winning, the enemy has tended to be, shall we say, less than ten feet tall. Three times in the last 60 years, U.S. forces have achieved an approximation of unambiguous victory—operational success translating more or less directly into political success. The first such episode, long since forgotten, occurred in 1965 when Lyndon Johnson intervened in the Dominican Republic. The second occurred in 1983, when American troops, making short work of a battalion of Cuban construction workers, liberated Granada. The third occurred in 1989 when G.I.’s stormed the former American protectorate of Panama, toppling the government of long-time CIA asset Manuel Noriega.

Apart from those three marks in the win column, U.S. military performance has been at best mixed. The issue here is not one of sacrifice and valor—there’s been plenty of that—but of outcomes.

… An alternative reading of our recent military past might suggest the following: first, that the political utility of force—the range of political problems where force possesses real relevance—is actually quite narrow; second, that definitive victory of the sort that yields a formal surrender ceremony at Appomattox or on the deck of an American warship tends to be a rarity; third, that ambiguous outcomes are much more probable, with those achieved at a cost far greater than even the most conscientious war planner is likely to anticipate; and fourth, that the prudent statesman therefore turns to force only as a last resort and only when the most vital national interests are at stake. …

To consider the long bloody chronicle of modern history, big wars and small ones alike, is to affirm the validity of these conclusions. Bellicose ideologues will pretend otherwise. Such are the vagaries of American politics that within the Beltway the views expressed by these ideologues—few of whom have experienced war—will continue to be treated as worthy of consideration. One sees the hand of God at work: the Lord obviously has an acute appreciation for irony.

… The impetus for weaning Americans away from their infatuation with war, if it comes at all, will come from within the officer corps. It certainly won’t come from within the political establishment, the Republican Party gripped by militaristic fantasies and Democrats too fearful of being tagged as weak on national security to exercise independent judgment. Were there any lingering doubt on that score, Barack Obama, the self-described agent of change, removed it once and for all: by upping the ante in Afghanistan he has put his personal imprimatur on the Long War.

Yet this generation of soldiers has learned what force can and cannot accomplish. Its members understand the folly of imagining that war provides a neat and tidy solution to vexing problems. They are unlikely to confuse Churchillian calls to arms with competence or common sense.

What conclusions will they draw from their extensive and at times painful experience with war? Will they affirm this country’s drift toward perpetual conflict, as those eagerly promoting counterinsurgency as the new American way of war apparently intend? Or will the officer corps reject that prospect and return to the tradition once represented by men like George C. Marshall, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Matthew B. Ridgway?

As our weary soldiers trek from Iraq back once more to Afghanistan, this figures prominently among the issues to be decided there.

Filed in Culture of Preparedness,Elements of Essential Information,Terrorism,What Kind of War,What Kind of War The Series | One response so far