Feb.22.2011

11:08 pm

by Ed Beakley

Washington – Commander, Leader: Petit Guerre, All the difference in the world

Boundary Condition #3 (2)

Preserve harmony, create chaos and achieve victory by continually keeping the enemy off balance through a superior capability to adapt. Sun Tzu

Today, February 22nd 2011 is George Washington’s birthday. As a country we don’t really pay homage to our first President, commander of the Continental Army or Father of the Nation. Rather what we do, is have Presidents Day which is intended to honor both Washington and Lincoln, and in reality is a Federal Holiday, day off for many, and opportunity for mass sales, the last being the most noted aspect.

For Project White Horse, this is an opportunity to continue discussion of the 2011 boundary condition focused on Washington’s leadership in trying times. The first post discussed the Battle of Trenton and its significance in American history in making the Declaration of Independence more than just fine words surrounding an abstract idea of “we the people.”

In the best noted modern research The Howe Brothers and the American Revolution, Ira Gruber concludes:

“Trenton and Princeton were supremely important in destroying the illusion of British invincibility, making patriots of potential loyalists, and spoiling Howe’s hopes for an end to the war and a start to a lasting reunion. Both General and Admiral Howe were forced to rethink their entire plan. General Howe wrote “I do not now see a prospect for terminating the war but by a general action, and I am aware of the difficulties in our way to obtain it.”

Indeed as David Hackett Fisher says in his Pulitzer Prize book, (the major source for this post) Washington’s Crossing, “By the Spring of 1777, many British officers had concluded that they could never win the war. At the same time, Americans recovered from their despair and were confident that they could not be defeated. That double transformation was truly a turning point in the war.”

What had occurred here since the dark days of mid-December when even many who signed the Declaration had become resigned to defeat?

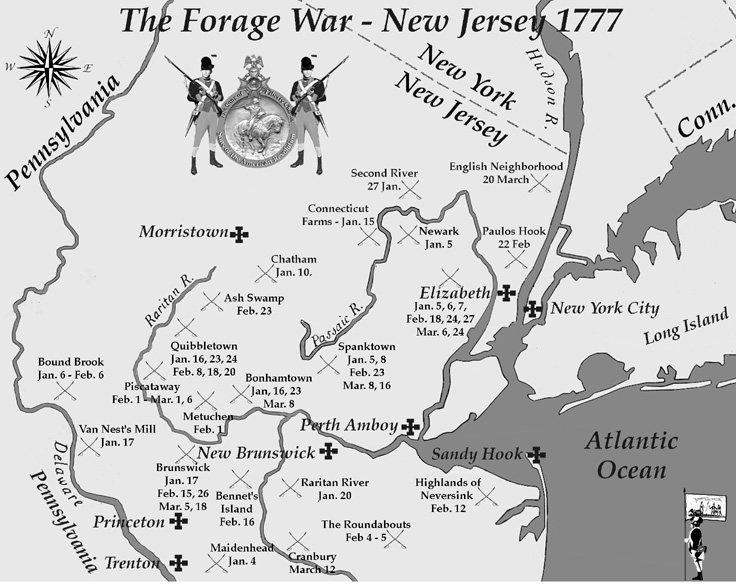

The answer lies in a little known portion of the Revolutionary War encompassing the “Forage War” or petit guerre, wherein the actions of both the Continental Army and the Jersey militias resulted in 2,887 of Howe’s British and German troops killed, captured or seriously wounded. By the end of that winter campaign more than half of all British and Hessian troops who had joined Howe’s army in 1776 were casualties – killed, wounded, captured, missing, dead of disease or so severely ill as to be officially reported as ineffective. On January 31stHowe had asked for 20,000 more troops but was informed by his government that he could expect 7,800. After Trenton and Princeton, after the January to March petit guerre, the British effort faced a chronic shortage of strength that continued throughout the remainder of the war.

While the Revolutionary War is not representative of unconventional crisis as defined, the period after the Continental Army retreat from New York in the summer of 1776 until the spring of 1777 does reflect a time of severe crisis, and one in which the total nature of the situation completely reversed. The elements of decision making and leadership that at the same time created novelty and confusion for the other side while enhancing vitality and growth for itself is certainly consistent with the previous post on the thoughts of John Boyd and therefore seem fair game for a study of decision making in severe crisis.

David Hackett Fischer historical analysis Washington’s Crossing provides the most research and critical analysis of the period surrounding the Battle of Trenton and the following period. This book is the major source for this effort. In even a casual reading of Fischer’s final two chapters, the idea of control of tempo and time as a weapon jumps off of the page. For almost three months the British and Hessian commanders were never able to get out of a reaction mode after Trenton.

Fischer’s analysis reflects well John Boyd’s ideas, not only control of tempo but also the aspect of OODA as a learning process for vitality and growth. In support of using Boyd’s way as instructive for decision making in severe crisis and in accord with Chet Richards question, “What type of organizations operate at rapid OODA loop tempos?” the elements of OODA will be used to organize Fischer’s conclusions. None of his conclusions are altered, they are just rearranged. As such, the intent is to suggest lessons for possible implementation for severe crisis decision making and leadership. All errors are mine and should not reflect on David Hackett Fischer’s original work.

Analysis

Observation > And of course, the best force multiplier is good intelligence. Lack of intelligence on British movement in New York was a major factor in the American loss in the New York campaign. In New Jersey, Washington was the central figure in developing a system of intelligence, personally recruiting agents with orders to report to him alone. He employed Nathaniel Sackett of the New York Committee for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies to construct an entire network in New York with both male and female agents of every rank and station. He also asked Continental generals and militia commanders to run their own agents. Although encouraging some degree of separation of these networks for security and broad based sources, his attitudes toward intelligence-gathering were different from those in closed societies, who sought to monopolize intelligence and prohibited efforts they did not control. Washington was comfortable with an open system permitting and even encouraging a high degree of autonomy.

With the efforts and results of multiple sources, the maneuvers of militia and regular Continental Army units were made much more effective. The best example may be the “Forage War” as the central focus of the Winter Campaign.

While Lord Cornwallis provided uniforms and food for his troops out of his own personal fortune, the British had a critical shortage – feed for its animals. Washington was quick to pick up that small numbers of men could do real damage to the British, reporting to Congress that intelligence reports “confirm their want of forage.. If their horses are reduced this winter it will be impossible to take the field in the spring.”

Orientation> Throughout the Revolution, George Washington’s strategic purposes were constant: to win independence by maintaining American resolve to continue the war, by preserving an American army in being, and by raising the cost of the war to the enemy. He was always fixed on these strategic ends but flexible in operational means. No single label describes his operations.

He learned to control initiative and tempo in war. Along with his officers he did more than merely surprise the Hessians garrison at Trenton the morning after Christmas. As the winter campaign continued beyond the Second Battle of Trenton and the Battle of Princeton, they improvised a series of surprises over a twelve week period, seizing initiative and keeping it. Recognizing the impact of the New Jersey militias, which at times frustrated him due to his lack of complete control, and realizing how effective many small engagements could be in reducing the fighting strength of the British and German regiments, he ordered most of his Continental troops to reinforce the Jersey Militia.

Understanding the critical role the Continental Army played not only in fighting battles but just in surviving as a fighting force, Washington himself did not take to the field in that critical January to late March ’77 time frame. Rather he was busy with recruitment of the new three-year regiments and expansion of the army for the spring campaign. Much of his time and energy went into relations with the members of Congress and leaders of the states. Critical war fighting decisions were on going in the Forage War, and Washington was at the center, but functioning as a leader of the republic, always listening, inspiring, guiding, urging his officers always to be the drivers of events, never “to be drove.” Continental brigadiers and militia commanders received independent commands with very broad instructions. Washington’s lieutenants like Horatio Nelson’s captains, knew what was wanted of them. Not only did it drive the British, force them to move in more troops than they could actually house and feed, it allowed the American army to learn and gain strength beyond numbers.

Decision> After Trenton and the surprise disengagement at the Second Battle of Princeton on January 2nd leading to the next day victory at Princeton, the thoughts of British commanders who in mid December thought they were on the verge of finishing the Continental Army were no longer about attacking but being attacked. Cornwallis ordered retreat and Howe’s generals began blaming each other. The British had no desire nor saw any advantage to seeking battle in the winter. Washington realized he could make a major impact with small attacks and limiting the potential of British mobility in the spring. The context of decision making changed drastically for both armies.

Throughout the British maintained the rigid hierarchal structure and command process of a European Army. By comparison, Lord Cornwallis ignored the advice of very able subordinates at the Second Battle of Trenton, while Washington listened and took the advice that led to the night disengagement and further victory at Trenton. While he did not begin the petite guerre begun by the Jersey militia, he cognized its potential and made a crucial decision to support it with Continental troops. Time and again, while the British were forced to react, Washington’s lieutenants, understanding their generals overall intent made the decisions to attack or disengage so as to continue to drive the British and German armies.

Another key decision, despite multiple incidents of maltreatment American troops by the British and Hessian armies, was Washington’s directions as to treatment of prisoners after the Battle of Trenton – they were to be accorded the same rights of humanity for which American’s were fighting. Supported by John Adams, American leaders believed that it was not enough to win the war. They also had to win in a way that was consistent with the values of their society and the principles of their cause. What Adams created in words and policy, Washington put into action. In comparison, British and Hessian commanders only selectively offered “quarter” to American troops attempting to surrender, and treatment of prisoners was routinely horrific. And as American success grew by in large British attitude and actions hardened, with unwanted consequence that resistance by Americans, some loyalists, grew stronger. Washington staked out the moral high ground, to the surprise of British and Hessian prisoners. Not all American leaders agreed, but in general the Continental Army’s adoption of Adam’s “policy of humanity” enlarged the meaning of the American Revolution.

While morale plummeted on one side, the Americans now knew how to fight and knew they could win. The performance has been judged one of the most brilliant in history.

Action> In the Winter ’77 Campaign/New Jersey Campaign and Forage War, American troops repeatedly defeated larger and better trained regular forces in many different types of warfare: what we now label special operations, maneuver warfare including a night river crossing and assault on an urban garrison, a fighting retreat, a defensive battle in fixed position, a disengagement to a night march into the enemy’s rear, a meeting engagement, and a prolonged petite guerre – the small war. The British on the other hand were on the wrong side of tempo, constantly harassed, forced to bring in more troops which exacerbated housing and feeding and spread of disease. Despite the maintenance of rigid command structure, British and German field commanders understood what was happening and attempted to lure the American militia and regular army into head on attacks or set ambushes for the attacks on foraging. But under mission type orders, Washington lieutenants continued to maintain initiative, disengage where necessary and even ambush the ambushers. By the spring of 1777, many British officers had concluded they could never win the war.

Synthesis

In the most desperate of struggles, Washington listened to and trusted his lieutenants, provided broad instructions with few direct commands, learned to leverage the emerging American culture and adapted. Not easy with the militias or their leaders, observation led to an orientation around usefulness of small units and harassing style warfare. Leveraging boldness, flexibility and opportunism, initiative and tempo, speed and concentration, and intelligence, he and his commanders defined a way of warfare that would continue throughout the war. Specifically leveraging “implicit direction, they drove the decision cycle in true reflection of John Boyd’s OODA Loop, finding a way to defeat a formidable enemy, not merely at Trenton and Princeton but over and over through twelve weeks of continuous combat. Fischer notes:

In New Jersey, American leaders learned to make time itself into a weapon. They did it by controlling the tempo and rhythm of the campaign. Day after day through the winter campaign, the Americans called the tune and set the beat. By that method, they retained the initiative for many weeks and kept British commanders off balance. The material and moral impact was very great, especially when a small force was able to control the tempo of war against a stronger enemy. Events happened at a time and place of their choosing. From all this another American tradition developed.

The context is pure John Boyd not only related to fast transients but also in context of Boyd’s theme for vitality and growth: insight, orientation, harmony, agility and initiative. Indeed in Washington’s Crossing, Fischer’s arguments mirror John Boyd’s as represented by Chet Richards in answering his question “What kind of organizations operate at rapid OODA loop tempo:

Organizations whose leaders have, over time, imbued certain qualities into the fiber of their very being, with these four qualities”

- Superb competence, leading to a Zen-like state of intuitive understanding. Ability to sense when the time is ripe for action. Built through years of progressively more challenging experience. Magic.

- Common outlook towards problems. Includes mutual trust. Built through shared experience. Superb competence and intuitive understanding at the organizational level. Values, doctrine, teamwork, mission.

- Concept that answers the question, “What do I do next?” in ambiguous situations. Gives focus and direction to our efforts. Key function of leadership.

- Understood and agreed to accountability. Conveyance to team members what needs to be accomplished, get their agreement to accomplish it, then hold them strictly accountable for doing it – but don’t prescribe how. Requires very strong common outlook.

In Patterns of Conflict, John Boyd defined a “unifying vision” as follows:

A grand idea, overarching theme, or noble philosophy that represents a coherent paradigm within which individuals as well as societies can shape and adapt to unfolding circumstances – yet offers a way to expose flaws of competing or adversary systems.

Washington’s grand vision was never more important than in that winter of 1776, ’77.

Filed in 2011 Boundary Conditions | Comments Off